August 7, 2010

No Soup for you

Recently the UBS compliance department took a look at my blog and made a judgment on whether or not, as a Strategist, I could continue writing on this thing. Sadly, the answer was no, unless I changed the subject to gardening or “showing my vacation pictures”. I was hoping that a disclaimer that “the views shared here in no way reflect those of XYZ” would solve any potential issues, but quite frankly I am not surprised. It’s a big bummer because I had a lot of fun with this blog, and there were a lot of subjects I looked forward to writing about in the future, especially labor mobility, the concept of human beings living and working where they please.

Maybe I’ll pick this up again in the future, or maybe I’ll find someone to take it over for me. Until then, I am contemplating starting a blog on another of my passions, which is religion, theology, and my experience as a Baha’i. Stay tuned for that, if it’s something that interests you.

Thanks to everyone who read this blog and posted their comments.

-Eamon

June 7, 2010

Optimization overload

Sendhil Mullainathan and others argue that in real life, individuals don’t costlessly process information in making their decisions. This should be blatantly obvious to all of us, yet it doesn’t seem to be for many policymakers. The fact is, this insight has more impact in our everyday lives that we’d like to think.

Like I mentioned in my last post, recently I attended the 10th anniversary of the founding of the Harvard Kennedy School’s MPA/ID program. This was an awesome spectacle in the middle of Harvard Square, with 10 classes worth of alumni from the development field (and others), some big-name guest speakers, and plenty of partying. Mostly, it was just great to see all my old classmates (even though we graduated only about a year ago). But it was also just nice to get back into the “classroom”, so to speak, and think about development again.

One of the most interesting parts of the weekend was a short presentation by Sendhil Mullainathan, the Harvard economist, as part of a panel discussion on “innovative finance”. Mullainathan summarized some of his and others’ research into why certain financial products and interventions fail in the developing world. The answer in some cases, he argued, was that people simply can not costlessly process the complex sets of information necessary to make certain financial decisions. This is especially true of the poor, and he gave the example of a particular fruit vendor. How can we assume that a woman who sells fruit for off of a cart for a living, and who doesn’t know what her income is going to be when she wakes up each morning, is going to properly calculate her expected annual income and decide optimally on a myriad possible consumption and saving choices?

In a summary of this line of behavioral research, Mullainathan writes:

In the standard economic model people are unbounded in their ability to think through problems. Regardless of complexity, they can costlessly figure out the optimal choice. They are unbounded in their self-control. They implement and follow through on whatever plans they set out for themselves. Whether they want to save a certain amount of money each year or finish a paper on time, they face no internal barriers in accomplishing these goals. They are unbounded in their attention. They think through every problem that comes their way and make a deliberate decision about each one. In this and many other ways, the economic model of human behavior ignores the bounds on choices (Mullainathan and Thaler 2001). Every decision is thoroughly contemplated, perfectly calculated, and easily executed.

As I’ve written on this blog before, it’s not the model that is faulty, it’s those of us who over-interpret the assumptions of the model — assumptions that are intended to achieve a mathematically useful result, not serve as a view of human nature — who are causing harm. Mullainathan argues that the standard model is limited if we are going to properly understand how the developing country poor interact with finance, and properly design policies and make rules.

I’ll take it one step further and argue that in the developed world, this is also a major issue, and that people who insist on the hyper-rationality of all human beings need to come down from their clouds and embrace reality. What Mullainathan and his colleagues have illustrated is at the very heart of why Americans, for instance, would benefit greatly from a Consumer Financial Protection Agency that protects individuals from intentionally confusing or misleading behavior on the part of financial institutions.

May 20, 2010

Big changes

There’s been quite a lot going on for me recently that has pulled my attention away from this blog. First and foremost, last month I got married and my wife and I were completely absorbed by the enormous requirements of planning a wedding. Afterwards, we took about nine days for our honeymoon (Costa Rica, which was loads of fun), but then came back to the post-wedding reality of gifts, thank-you cards, unpacking, and other miscellaneous starting-life-together duties. It’s been fun, but it’s sucked me away from the blog as well as other things.

The other big change is my job. I’m in my last few weeks at my current auto insurance role and will be joining an emerging markets strategy team in mid-June. Since a lot of what I’ll be doing is based on macro trends and global markets, this might mean that the subject matter for the blog will have to be dramatically narrowed. I’ll figure this out some time in the next few weeks.

For now, there are a handful of topics I’ve been daydreaming about writing about:

– Labor mobility

– Auto insurance and signaling

– Last weekend’s MPA/ID 10th year anniversary (some interesting presentations, hoping to write down some of my reflections)

If this blog is going to be axed or neutered in a month, I’ll have to try and get everything in. Stay tuned.

April 4, 2010

Nerd-on-nerd mega-battle for smartphone supremacy

I can’t help noticing the Motorola Droid ads these days, mostly on TV and on billboards, and how strikingly different the product’s marketing strategy is from that of the iPhone. It’s remarkable, because from what I understand the Droid is an impressive product, perhaps the most impressive smartphone since the iPhone was released back in the summer of 2007.

I can’t help noticing the Motorola Droid ads these days, mostly on TV and on billboards, and how strikingly different the product’s marketing strategy is from that of the iPhone. It’s remarkable, because from what I understand the Droid is an impressive product, perhaps the most impressive smartphone since the iPhone was released back in the summer of 2007.

Motorola and Google are promoting the Droid as raw horsepower-in-a-handheld. Their catchy slogan, which calls the Droid a “bare-knuckled bucket of does”, along with the TV ads featuring automated robot hands presenting in a rugged black backdrop, seems like the very opposite of Apple’s marketing strategy for the iPhone (or pretty much any of their products).

My first reaction to the ad campaign was to view it as just another example of tech companies failing to understand the customer and how that customer uses technology. The “user experience” which Apple understands so well and so masterfully weaves into its product design and marketing is where other PC and electronic good manufacturers have so famously fumbled. In the 1990s we saw a race, famously won by Dell via its revolutionary supply chain, to provide the PC with the greatest specifications at the lowest price. Unfortunately that game proved barely profitable, and even the winners like Dell ended up losing on the bottom line.

I didn’t fully get how bad Apple was abusing its competition in the user experience game until I interned there as an MBA student in the summer of 2007, the same summer the iPhone was launched. Almost weekly, the interns gathered to listen to a top executive speak, and by far the most interesting lecture was delivered by Johnny Ive, Apple’s user experience guru. One of his most entertaining stories was about developing the look and feel of the original iMac, which famously had a handle on the top. The handle, he explained, wasn’t to carry the computer around easily. It was to invite people to reach out and touch the computer and become phy7sically acquainted with it, after research had revealed a major psychological comfort barrier between the user and the machine.

It was amazing how most of us back at Sloan failed to get this. When we came back from our winter break the same year, we discussed the recently-unveiled iPhone in our first Strategy class. The idea got totally blasted. Margins in the mobile device sector are razor thin. They’ll cannabilize the iPod. And Apple just doesn’t do phones. I heard something similar about a year later, while waiting for an interviewer in a hotel lobby with some other Sloan students. One of them was chatting loudly with his friends about Apple computers. “They get killed in pretty much all the specifications!” he said confidently, apparently referring to hard drive size, RAM, processor speed, etc. He must have forgotten about the specification about whether or not people actually understand and enjoy using their computers.

Have the Droid people totally missed this? It seems like they have, although it’s hard to believe they could actually miss something so obvious, especially when Google is involved. When your marketing strategy is to present the product with black robot hands, who do you envision buying the product? And how well does this message resonate with the the dozens of millions of people who are forecasted to use smartphones for the first time in the next few years?

I don’t get it. But of course, it’s entirely possible that I’m missing something, and the Droid marketers are smarter than I think. Or maybe they’ve recognized that Apple does easy-and-approachable so well that the only people left to market to effectively are the tech geeks, and the guys drinking vodka with sexy robots.

March 30, 2010

Fear of falling: Why the dollar is (thankfully) destined to fall further

Recently I’ve heard people lamenting the weakness of the dollar, and fondly reminiscing about the good-old-days in the 1990s, when the dollar was historically strong against other currencies. I have to admit that even I wish I could go back to just a few years ago when I would drive up to visit my girlfriend (now fiancé) in Montreal, and get a huge plate of Lebanese food for about seven bucks. When your life is largely motivated by the search for cheap delicious food, the weaker dollar has made tourism a serious drag.

Within the past two years the dollar’s value has taken us for a particularly curious ride. Through much of 2008 it actually appreciated, as global investors fled to the safety of the dollar amid financial crisis (one of the few times in history, I imagine, that a country went through a financial crisis and demand for its currency actually increased). Then dating back to about 12 months ago it started a steep decline, and that’s when the exchange rate panickers came out again in full force.

When it comes to public perceptions, exchange rates constitute one of the worst-understood topics in economics. Many bright people fall into the trap of thinking “strong dollar: good; weak dollar: bad”. The simple truth is that weak can be as good or better than strong, depending on what you want or what you need . If you want to buy lots of foreign goods, then strong dollar: good. If you want to sell more of your goods and services to foreigners, then it’s actually weak dollar: good. In reality, a free market does a great job of getting you to a not-too-strong, not-too-weak equilibrium of the value of a country’s currency. (Of course, if you’re a small developing country with an inflation problem, then there are other factors at play.)

Despite the decline in the value of the dollar against most currencies over the past ten years or so, I personally believe there is still no way to go but down from here for the next ten. The rest of this blog is about explaining a) why I feel that way, and b) why this is actually a good thing.

February 2, 2010

The Popular Thing to Do

It’s rare that the right thing to do economically is also the popular thing in the eyes of the general populace. But that’s exactly what seems to be the case with some of the proposed banking reforms. So why isn’t reform easier?

The proposed financial reforms announced by President Obama — including new rules to limit the size of “too big to fail” banks that create moral hazard — has been casually referred to by commentators in TV and print as “populist”. The most common argument is that now that the Democrats lost the special senate election in Massachusetts, they’ve got to pander to the American public by demonizing the easy-target banks. But now there are a handful of people challenging this, arguing that just because something is popular, that doesn’t make it populist.

One of those people is Simon Johnson, former chief economist at the International Monetary Fund who’s now at MIT Sloan (where else). He wrote in Baseline Scenario recently:

“The fact that dramatic banking reforms would be popular does not make them populist. It merely means that a broad cross-section of our population has woken up to part of our appalling reality. Sure, they are angry – but with good reason, and the remedies they seek are entirely appropriate.” (Full entry here.)

I don’t want to make this blog a political forum, but I have to unequivocally side with Simon Johnson 100% on this one. He’s been right on this issue for months. The president is now experiencing a policy that has that rare combination of overwhelming popular support and actual policy integrity. People are angry at the near-fatal financial collapse and the enormous bail-out and stimulus funds needed to avoid an economic cataclysm. Now we have nearly every famous economist making the case that without serious financial reform, we’re bound to face a “doom loop” of collapse and bailout until the problem is fixed.

So don’t call this particular popular policy “populist”. There are plenty of policy ideas floating around — even in this country — that deserve that tag.

The only question is: If financial reform is both politically and economically smart, why isn’t it a sure thing? To understand this one, consider that by some estimates the biggest four American banks now hold about half of the nation’s deposits and two-thirds of credit card balances. Then read my last entry.

January 23, 2010

What we have here is a failure to coordinate

Why does the recent ruling by the US Supreme Court on corporations and political influence strike us as so potentially dangerous? The answer lies not in the legal side of the issue, but rather the economics of how individuals consolidate to influence decisionmaking.

It’s clear to me that from a legal perspective, both arguments on this issue have validity. The point argued by a slight majority (five of nine justices) — that corporations are entitled to First Amendment protections and thus can not be differently restricted in their political contributions — is hard to refute, if one focuses on the language of the Constitution itself. Nonetheless, one could easily respond that this was never the intention of the authors of the Constitution, and that the ruling would have destructive effects on democratic institutions. The complexity of the issue is summed up by the words of Justice John Paul Stevens, who sided against the court’s decision. Stevens conceded that “we have long since held that corporations are protected by the First Amendment”, but ultimately concluded that “the court’s ruling threatens to undermine the integrity of elected institutions around the nation”.

But regardless of the legal correctness of the ruling, there is the issue of ruling’s actual effects, and this is where many of us feel a chill down our spines. We imagine a world where corporate interests have even more sway in legislation than they have now, and the voices of individuals are drowned in a sea of lobbies and interest groups. But is this really what will happen? Wouldn’t a free market for information produce the best possible political decisions, just as it does in goods markets? The argument is that if the market for information and political influence are free, then the elements with the most to gain will push and spend the hardest to get their policy choices to the front in Washington. Just like people vote with ballots, the free market allows the nation to vote with dollars. At least that’s how the narrative reads.

Most people with sense, however, take a look at American politics and realize that this narrative doesn’t quite play out in real life. There seems to be something getting in the way of this neat and just market scenario, and skewing the distribution of influence towards the big players. But most of us can’t really put our finger on what that something is.

December 14, 2009

APRrrrrrr

If you’ve been following this blog in the past couple months, you’ll know that I’m a pretty adamant critic of marketing and advertising methods which seem to prey on consumers’ lack of knowledge or judgment. This past summer I wrote an entry about this, in the context of advertising. The premise was that though classical economic models rest on the principle of rationality, recent research (and common sense) argues convincingly that people really don’t behave that rationally. (This is not an indictment of economics, which purposefully simplifies life to provide a useful model, but rather those people who get obsessed with these simplifying assumptions and begin to believe they actually play out in real life.)

If consumers aren’t really rational, I argued, then producers could find ways to exploit that lack of rationality with clever tricks and gimmicks. As I discussed earlier, if you don’t believe this is possible, just one piece of evidence is Bertrand et al’s experiment in South Africa, where men were shown to be significantly more likely to accept a loan offer when a woman’s face appeared on the promotional material. Behavior on the part of firms that targets consumers’ irrationality is so common, I argue, that we barely bat an eyelash at the bikini babes used to sell beer on TV, or asterisks on big “50% off!” signs with fine print at the bottom.

An ad from uvacreditunion.com. Few people, it seems, know the difference between APR and APY interest rates.

This type of behavior would be fine if the influence it has was distributed evenly across types of goods, but that is unfortunately not true. There are some industries or products for which such messages are enormously powerful, and others where they are not used at all. So you end up with a world where the consumption of things that can be effectively advertised with persuasion is too much, and the consumption of things that can’t is too little.

One industry that is great at this is credit cards. I don’t think credit card companies necessarily utilize the emotional cues that I talked about in my earlier post any more than any other industry. But they have mastered the art of confusing consumers and overwhelming them with seemingly impossible-to-understand information. One of the silver linings of the financial crisis (especially relating to subprime mortgages), I think, is that it raised awareness of the need to protect the consumer when it comes to personal finance.

Let’s look at one of the simplest and seemingly most innocuous examples of this: the clever use of APR and APY interest rate quoting standards. If you don’t know already, the principle difference between APR (annual percentage rate) and APY (annual percentage yield) is that the first one doesn’t count compounding in the number, while the second one does.

October 30, 2009

Islam by the numbers

I have a good grad school friend named Adam (not his real name) who’s from a predominantly Muslim country but is harshly critical of Islam. Like many countries in the Middle East and Central and Southwest Asia, Adam’s country is developing but moving slowly in certain regards, and threatened by the possibility of catastrophic collapse. It is a burgeoning democracy, but (by most measures) suffers from poor governance and widespread corruption. It has millions of moderate, peaceful Muslim believers who care more about their families’ wellbeing than politics, yet violent islamists are growing in strength within the country.

Adam and I have a usual ironic pattern to our arguments. It usually involves him (Muslim, at least by family) arguing how terrible Islam is while I (not Muslim but very respectful of Islam) defend it. Usually the arguments are about some aspect of Islamic history or doctrine (for instance, where Adam will raise the example of some hadith where the Prophet Muhammad said such-and-such ridiculous thing, and she sheer ridiculousness allegedly proves Islam’s falsehood).

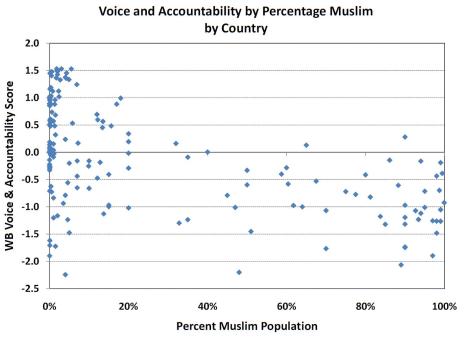

To Adam, though, Islam is not just a false religion, but it represents a movement and belief system that is actually harmful to his country’s progress. Recently, we argued over email from 8,000 miles apart about this, when Adam pointed out how poor female labor force participation is in many Muslim countries. This isn’t an opinion, but a fact; in reality, Muslim countries perform very poorly on a wide range of social indicators. Below is a scatter plot, just to provide a visual example, with World Bank Voice & Accountability scores on the y-axis, and the proportion of countries’ populations being Muslim on the x-axis. The downward sloping relationship is pretty visible here.

However, making the jump to the conclusion that Islam somehow causes these poor social outcomes (or anything else) is something that no sensible person, including Adam, would do. Adam’s argument was based both on the data and on anecdotal evidence from his own life. On the contrary, rather, it is possible (likely) that the prevalence of Islam happens to be correlated with some other factor that is driving these outcomes.

September 29, 2009

Economic forecasting with household items

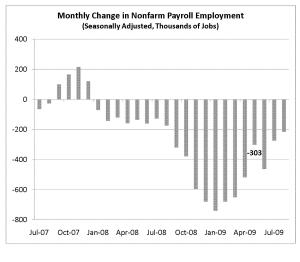

For a while I’ve wanted to just do a quick forecast of employment with “household” items (basically anything you can find on the web). So I took a stab at it. The basic question I sought to answer was what the quarterly employment change (change in seasonally-adjusted, non-farm payroll employment) will be in six months.

Why is this interesting? Well, if you look at the last few months’ worth of employment change data, it’s tough to figure out just what the next few months have in store. Job losses seamed to peak (or trough, whatever) back in January, when the US economy lost about 741,000 jobs on a seasonally adjusted basis. In the next four months we saw this number steadily decline to just 303,000 in May, and everyone got excited. Then the next month it jumped back up to 463,000 in job losses, still a devastating number and pretty disappointing for those that hoped we’d reemerge into positive territory soon.

Now I feel that analysts don’t really know what to expect from the next few months. Will we continue to shed employment at a lower level for much of 2010? Will the numbers reach into slightly positive territory or hover around zero for a while, at a pace of growth slower than that of the labor force? Or will employment rebound strongly in the next few months, enough to bring down the unemployment rate? (Unfortunately, not many people seem to believe in this last scenario.)